5月末,我在微信公众平台“夹山改梁 Jasagala”上发表了一篇以《地方美术学院本科毕业展》为题的文章。这篇关于美术学院本科毕业作品的推送完全由机器学习所自动生成。其中的学生照片,姓名,作品图片,作品标题,作品阐述,全部都是由ChatGPT和Midjourney在我的引导下自动完成,并没有任何后期的手动修改。没曾想几小时内就突破了十万阅读,并不断攀升。我在此之前也发表过类似的文章。但是以往的这几篇文章仍只停留在我们已有的读者圈子中,并未被摆放到公众层面来进行讨论。刚好《画刊》的孟尧先生邀请我写一篇基于此事件的专栏,我也正好借此机会来聊聊我对人工智能、学院教育、原创与风格等问题的一些拙见。

At the end of May, I published an article titled “Local Art School Undergraduate Exhibition” on the WeChat public platform “Jasagala”. This post about the undergraduate final works of the art academy was entirely generated by machine learning. The student photos, names, work images, work titles, and work explanations were all automatically completed by ChatGPT and Midjourney under my guidance, without any manual modifications afterwards. Unexpectedly, it broke through a hundred thousand reads in a few hours and kept rising. I had also published similar articles before. However, those articles remained only within our existing reader circles and were not brought to the public for discussion. Coincidentally, Mr. Meng Yao of “Pictorial” invited me to write a column based on this event. I took this opportunity to share my humble opinions on issues such as artificial intelligence, academy education, originality, and style.

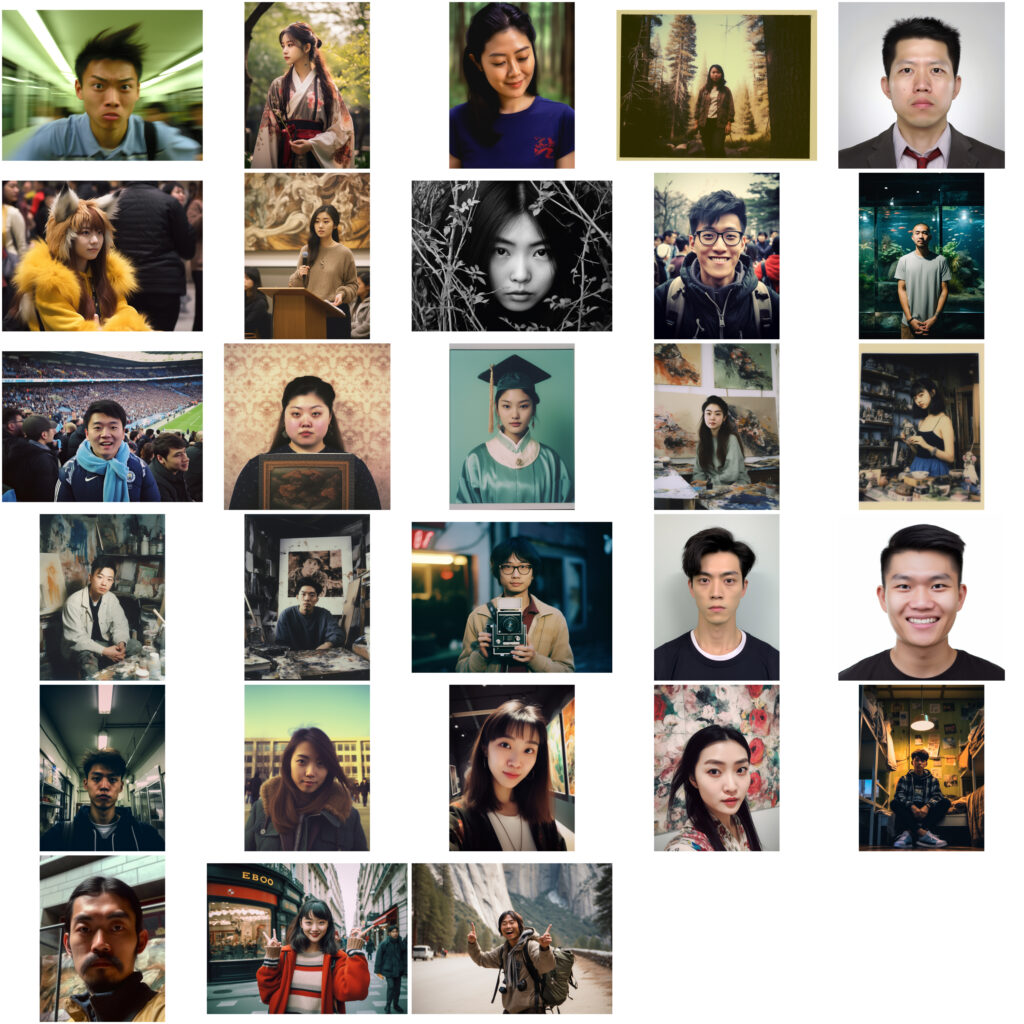

这篇推送的图文创作过程和我一开始所设想的其实略有出入。最开始我的设想是直接将真实存在过的学生作品作为图片提示词,但后来还是决定用纯文字提示词(prompt)作为唯一的生成源,效果居然意外的不错。比较花时间的部分反而是作者照片这块(图一)。在保持真实性的前提下尽量做到多样性并非一件易事。归根结底可能还是因为人脸是人类最为熟悉与敏感的图像信息。

The process of creating the graphics and text for this post actually deviated slightly from my initial idea. At first, my idea was to directly use existing student works as image prompts, but later decided to use pure text prompts as the only source of generation. The result was surprisingly good. The part that took more time was the author’s photo (Figure 1). Striving for diversity while maintaining authenticity is not an easy task. Ultimately, it might be because faces are the most familiar and sensitive image information to humans.

图一 Figure 1

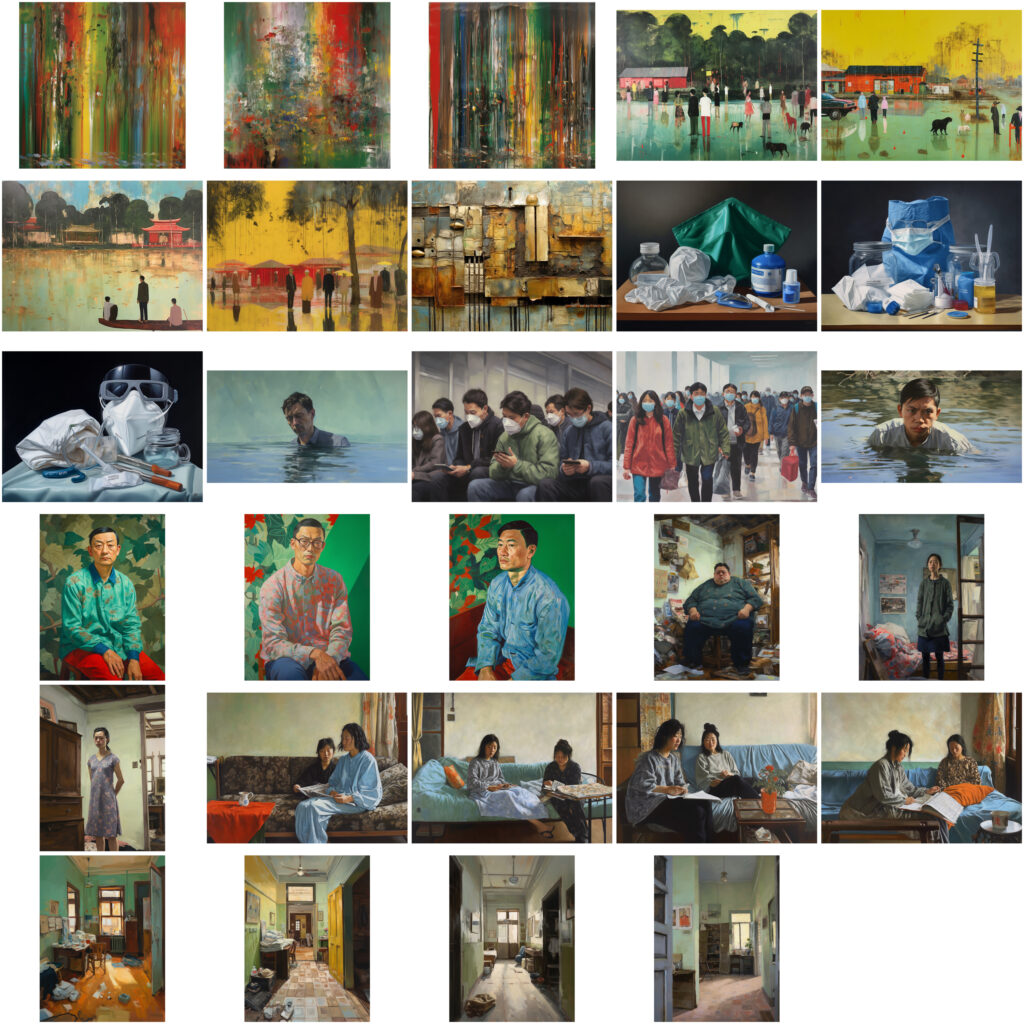

绘画与雕塑部分其实是最容易生成的(图二)。绝大部分的情况下,我只需几个关键词写出作品中大致的内容,再加上一到两个知名艺术家的名字,如里希特、彼得·多伊格、刘小东、大卫霍克尼等。

The painting and sculpture part was actually the easiest to generate (Figure 2). In most cases, I only needed to write a few keywords describing the general content of the work, plus the names of one or two well-known artists, such as Richter, Peter Doig, Liu Xiaodong, David Hockney, etc.

图二 Figure 2

作品简介部分,我则是在使用GPT4的基础上,花了非常多的前期准备功夫,通过不断的对话来构建出了一个符合我要求的语境。基本上,我需要提前对于作品解释的深奥程度以及其多样性进行细致的筛选和设定。而之后我将使用三个左右的关键词得到作品阐述。例如,对于传统的媒介,我会倾向于让作品描述保持比较简单的状态;然而,对于新的媒介,我期待其阐述“稍为晦涩”;至于人文学院,则是“美术史语境,需要极为晦涩难懂,并包含哲学家与学术名词,并用德语标注”。(表一)

For the work introduction part, I spent a lot of time preparing in advance based on using GPT4. I built a context that met my requirements through continuous dialogue. Essentially, I had to meticulously filter and set up in advance the depth and diversity of the explanation of the work. After that, I would use about three keywords to get a work explanation. For example, for traditional media, I tend to keep the work description fairly simple; however, for new media, I expect its explanation to be “somewhat obscure”; as for humanities colleges, it is “art historical context, needs to be extremely obscure and contain philosophers and academic terms, and be annotated in German.” (Table 1)

| 传统媒介 | 新媒介 | 人文学院 |

| 作品简介:《北方的冬》是我对姐妹间深深的情感和中国北方冬季室内生活的再现。我与妹妹在家中的一切,都成为我绘画的源泉,这是一种深深的人文关怀和对于中国传统居家生活的热爱。在画面中,我尽力去捕捉我们的笑声,以及那些温暖的室内空间:熟悉的木质家具,热气腾腾的暖气,和窗户上凝结的冰花。我将这些细节逐一记录下来,试图通过它们传递北方冬天的室内生活的氛围和情感。这些细节虽然微小,但对我来说,它们构成了一种我们生活的独特方式,是我身为中国人的身份的一部分,也是我对这个世界的理解。 作品简介:在《无声》中,我以无人的房间作为画面的主题,试图捕捉和表达在日常生活中常被忽视的静谧感。无人的房间,没有喧闹和嘈杂,只有静静的家具和被遗忘的物品,它们讲述着无声的故事。我试图通过作品的细节,揭示那些似乎寂静无声却又饱含深意的空间,从而引发对日常生活中那些被忽视、被遗忘角落的反思。我希望,通过观看这幅作品,人们能更多地意识到日常生活中潜移默化的影响,并开始珍视那些在嘈杂中被遗忘的静谧时刻。 | 作品简介:《季节游戏》既是一次行为艺术的表演,也是一次对人类感知与环境关系的探索。在夏季炎热的阳光下,我选择以兜售寒意的方式试图打破常规的季节感知。寒意在此,既是一种物理状态,也具有象征意味,暗指内心深处的情感与思考。通过这样一种对抗的方式,我试图破解我们对季节感知的固有认知,并重新审视我们与环境的互动方式。这个作品是对感知、体验和意义的一次深度探索,让观者在其中得以反思我们如何认识世界,如何理解生活。 作品简介:《纵横交错的寓言》并非寻常的视觉篇章,而是对于存在的微妙描摹,试图在显瞭与隐晦之间找到一个平衡。借由四元素——水、火、土、风,我置身于一个充满可能性的剧场,将观者引向元素交织的场域。那里的水火相济,风土相依,既隐喻着内在的心灵漩涡,又反映出外在的生存困境。这些元素在舞台的纵深中游弋,宛如人性的多重镜像,它们的存在即是我们内心深处的投射。我希望观者在观看时能捕捉到那些在剧场的灯光下短暂闪耀的元素碎片,它们或许能引导我们对存在和意识的本质有更深的理解。 | 标题:《寻踪阿伊努族意识形态与后法兰克福学派视野下的反思:对异质文化碰撞的深层解构》 论文概述: 本文将以后法兰克福学派的批判理论为基石,对阿伊努族的独特文化及其意识形态进行全方位的深度解析。通过这种思想碰撞,试图揭示它们之间可能存在的隐形连接,进而重新定位两者在现代社会文化格局中的地位。 首先,本文将从阿伊努族的社会文化现象出发,尝试理解其意识形态是如何形成并通过特殊的文化符号传递的。对此,我们将采用后法兰克福学派的“交往行动理论”(Kommunikatives Handeln)进行解构,以揭示在这种独特文化中隐藏的社会力量。 然后,我们将引入后法兰克福学派的“消费社会”(Gesellschaft des Konsums)观念,以理解阿伊努族的文化特征是如何在现代消费社会中保持其独特性。进一步的,我们将利用哈贝马斯的“系统与生活世界”(System und Lebenswelt)理念,探讨在现代社会系统压力下,阿伊努族的生活世界是如何应对和转变的。 最后,本文将尝试从批判理论的角度,对阿伊努族的文化现象进行进一步的解读和反思。借此,我们期望能以“文化多元论”(Multikulturalismus)的视角,重新理解异质文化的价值与意义,并对现代社会的多元文化交流与碰撞提供新的思考。 |

| Traditional Media | New Media | School of Humanities |

| Work Introduction: “Northern Winter” is a reenactment of my deep affection between sisters and the indoor life of northern China in winter. Everything between my sister and me at home becomes the source of my painting, showing a deep humanitarian concern and love for traditional Chinese home life. In the picture, I try to capture our laughter and those warm indoor spaces: familiar wooden furniture, steaming heating, and ice flowers condensing on the windows. I record these details one by one, trying to convey the atmosphere and emotion of indoor life in the northern winter through them. These details may be small, but for me, they constitute a unique way of our life, a part of my identity as a Chinese, and also my understanding of the world. Work Introduction: In “Silence,” I use an empty room as the theme of the picture, trying to capture and express the sense of tranquility that is often overlooked in daily life. The empty room, without noise and clamor, only has quiet furniture and forgotten items, which tell silent stories. I try to reveal these seemingly silent but deeply meaningful spaces through the details of the work, thereby provoking reflection on those overlooked, forgotten corners in daily life. I hope that through viewing this work, people can become more aware of the subtle influences in daily life, and begin to cherish those quiet moments that are forgotten in the noise. | Work Introduction: “Seasonal Games” is both a performance of performance art and an exploration of the relationship between human perception and environment. Under the hot summer sun, I choose to sell coldness in an attempt to break the conventional perception of seasons. Here, coldness is both a physical state and a symbol, indicating deep emotions and thoughts. Through such a confrontational approach, I try to decode our inherent cognition of seasonal perception and re-examine our interactive methods with the environment. This work is a deep exploration of perception, experience, and meaning, allowing viewers to reflect on how we understand the world and interpret life. Work Introduction: “Intersecting Fables” is not a typical visual chapter, but a subtle depiction of existence, trying to find a balance between the explicit and the obscure. Borrowing from the four elements – water, fire, earth, wind, I place myself in a theater full of possibilities, leading the viewer to a field intertwined with elements. There, water and fire coexist, wind and earth rely on each other, metaphorically representing the inner emotional whirlpool, and reflecting the external survival predicament. These elements swim in the depth of the stage, like multiple images of human nature, their existence is a projection of our inner depths. I hope that viewers can catch those fragments of elements that briefly shine under the theater lights while watching. They might lead us to a deeper understanding of the essence of existence and consciousness. | Title: “Tracing Ainu Ideology and Reflections under the Perspective of the Frankfurt School: A Deep Deconstruction of Heterogeneous Cultural Collisions” Thesis Overview: This paper will base its analysis on the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, providing an all-encompassing and in-depth examination of the unique culture and ideology of the Ainu people. Through this ideological collision, it attempts to reveal the possible hidden connections between them and subsequently reposition both within the cultural patterns of modern society. Firstly, this paper will start from the socio-cultural phenomena of the Ainu people, attempting to understand how their ideology is formed and transmitted through unique cultural symbols. For this, we will employ the Frankfurt School’s “Theory of Communicative Action” (Kommunikatives Handeln) for deconstruction, aiming to reveal the social forces hidden within this unique culture. Then, we will introduce the concept of the “Consumer Society” (Gesellschaft des Konsums) from the Frankfurt School, to understand how the cultural characteristics of the Ainu people maintain their uniqueness within the modern consumer society. Further, we will use Habermas’s concept of “System and Lifeworld” (System und Lebenswelt) to explore how the lifeworld of the Ainu people responds and transforms under the pressure of modern societal systems. Finally, the paper will attempt to further interpret and reflect on the cultural phenomena of the Ainu people from the perspective of critical theory. By doing so, we hope to understand anew the value and meaning of heterogeneous cultures through the lens of “Multiculturalism” (Multikulturalismus), and provide fresh insights into multicultural exchanges and collisions within modern society. |

然而,这篇微信推送文章,或者说这件作品,它的出发点其实并不完全是关于人工智能,而是落脚于艺术教育系统。早在好几年前,我其实就试图做类似这样的尝试。不过受制于实施难度与时间的限制,一直只悬停在脑海之中,没能将这个想法在现实层面落实下去。我对于艺术学院的教育有一种仿佛轮回了千万遍的倦怠之感。这种倦怠不仅仅只是针对学生创作的内容或形式,更是在学院教育本身。我曾就读于央美附中,后保送至央美造型学院,接着去到加州大学洛杉矶分校读研,随后在美国留校担任讲师至今。不知不觉在艺术学院的教育系统中已经待了十多年了。记得在央美读本科时,我和我的同学们差不多已经能准确预测每届每个院系,甚至每个工作室作品的面貌,风格,创作的主题,内容,以至于新媒介的比例。如果到了展览现场,则是几乎20米开外就能认出是哪个工作室的作品。在随后接触机器学习的过程中,我也获得了一些新的视角去思考,去反思何为新,何为教育。

However, this WeChat article, or this work, its starting point is actually not entirely about artificial intelligence, but it’s rooted in the art education system. Several years ago, I was already attempting something like this. However, due to the difficulties of implementation and time constraints, it was always just a thought that couldn’t be realized. I feel a sense of fatigue from art school education, as if I’ve been through it millions of times. This fatigue is not just about the content or form of student creation, but more about the education system itself. I studied at the Central Academy of Fine Arts Middle School, then went to the School of Plastic Arts of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and later went to UCLA for my master’s degree. I have now been a lecturer in the United States for several years. I have been in the art school education system for more than a decade. I remember when I was studying at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, my classmates and I could almost predict the appearance, style, and themes of works from each department and even each studio. If you went to the exhibition site, you could recognize which studio the work came from almost 20 meters away. In the process of learning about machine learning, I also gained new perspectives to think about and rethink what is new and what is education.

在机器学习中有一个叫做“过拟合“的概念。大部分情况下,生成式机器学习就是根据现有的数据集,寻找一个可以生成接近原数据样本的新数据的函数。但是,如果作为输入源的样本太少或者多样性太差,当一个模型过度复杂时,可能会过于适应训练数据中的随机误差或噪声,而不是背后的潜在关系。过拟合的模型在训练数据上表现优秀,准确率高,但是当应用到新的、未见过的数据上时,其预测性能通常会下降。原因在于该模型已经“记住”了训练数据中的特定噪声和异常值,而非学习到数据背后的真实趋势和模式。

In machine learning, there is a concept called “overfitting.” In most cases, generative machine learning is about finding a function that can generate new data that is close to the original data based on an existing dataset. However, if the input samples are too few or lack diversity, when a model is too complex, it may overadapt to the random errors or noise in the training data, rather than the underlying relationships. Overfitting models perform well on training data and have high accuracy, but their predictive performance often decreases when applied to new, unseen data. The reason is that the model has “remembered” the specific noise and outliers in the training data, rather than learning the real trends and patterns behind the data.

在根源上,这批机器生成的毕业作品之所以在风格和表现上与真实作品如此接近,实际上是因为在艺术教育,甚至更广义的人类学习过程中,我们极易陷入类似于机器学习中过拟合的困境。如果将前辈们的创作脉络视为训练的数据集,我们通常也会从模仿开始,学习前人的风格。每种风格都可能意味着多种创作策略的复杂组合。批评家、艺术史学家亚瑟·丹托曾经在1964年《艺术世界》中提出过一个叫做风格矩阵的概念。简单来说,风格与风格之间,在艺术界这个场域内,会形成一种或肯定或否定的关系。从一个简化的角度出发,如果我们只考虑“再现”与“表现”这两个维度,那么我们大致得到四种风格:野兽派(再现,表现),新古典主义(再现,非表现),抽象表现主义(非再现,表现),硬边抽象(非再现,非表现)。沿用这种思路,我们可以将某种流派或者某位艺术家的创作风格以关键词形式分解。例如,我们可以笼统去拆解刘小东的创作风格:

Fundamentally, the reason why these machine-generated graduation works are so close to real works in style and performance is because, in art education, and even in the broader human learning process, we easily fall into a predicament similar to overfitting in machine learning. If we consider the creative trajectory of our predecessors as a training dataset, we usually start by imitating their style. Each style may mean a complex combination of various creative strategies. Critic and art historian Arthur Danto proposed a concept called the style matrix in The Art World in 1964. Simply put, there is a relationship of affirmation or denial between styles within the art world. From a simplified perspective, if we only consider the two dimensions of “representation” and “expression,” then we generally have four styles: Fauvism (representation, expression), Neoclassicism (representation, non-expression), Abstract Expressionism (non-representation, expression), Hard-edge Abstraction (non-representation, non-expression). Using this line of thinking, we can decompose the creative style of a certain school or artist into keywords. For example, we can roughly deconstruct Liu Xiaodong’s creative style:

刘小东 ≈ 现实主义题材+写实主义画面表现+中等尺寸笔触+摄影视角+非制作性+油画材料性+中高饱和鲜灰色调+低差异性饱和度+高色相差异性+中高明度……

Liu Xiaodong ≈ Realistic subject + Realistic pictorial representation + Medium-sized brushwork + Photographic perspective + Non-production + Oil painting material + Medium to high saturation gray tone + Low saturation difference + High hue difference + Medium to high brightness …

回到机器学习的语境,这些正极负极的碎片化风格就成为了制作图片所用到的文字提示词。换句话说,写提示词在这个语境中基本上就是艺术创作的全部内容。并且,其实早在人工智能出现之前,就已经有很多人通过输入提示词与调参进行艺术创作。比如罹患帕金森后找人代笔的画家,不直接参与摄影或剧本创作的导演,以及无法亲自操弓的音乐指导。

Returning to the context of machine learning, these polarized, fragmented styles become the textual cues used to create images. In other words, writing cues in this context is essentially the entire content of artistic creation. Moreover, long before the advent of artificial intelligence, many people were creating art by inputting cues and tuning parameters. For example, a painter who had someone else paint for him after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a director who doesn’t directly participate in photography or script creation, and a music director who can’t personally handle the bow.

然而,这里面如此庞杂的对于多种创作手法的选择,更多的则是一种艺术家的主观判断,而非创作上的金科玉律。但当许多学生开始学习时,则是进入了一种对于整体风格全盘照收的惰性学习之中。一方面是因为他们在创作经验上无法分辨,但更重要的另一方面则实为一种潜移默化下的生存策略。齐白石曾经说过“学我者生,似我者死”。然而,在学院教育之中,画的像自己的老师并不是一件值得批评的事情。我曾亲眼见过美院的老先生去参观年轻教师的群展,然后把几乎每个人的作品都批评了一遍。而唯一有所肯定的作品的评价则是“画的挺像徐芒耀的”。很多时候,学术怕的并不是被人评价自己画的和老师太像,反而是怕自己的作品进入市场或体制的过程中,因为作品不像自己的老师,而失去了原本可以享受的竞争优势。这是一种默契,更是一场共谋。

However, the complex array of choices about various creative methods in this context is more of an artist’s subjective judgment, rather than a golden rule of creation. But when many students start learning, they enter a mode of passive learning that accepts the overall style wholesale. On the one hand, it’s because they can’t discern in terms of creative experience, but more importantly, it is a survival strategy subtly inculcated. Qi Baishi once said, “Those who learn from me will live, those who imitate me will die.” However, in academic education, painting like one’s teacher is not something to be criticized. I’ve personally seen old professors from art academies visiting the group exhibition of young teachers, and then criticizing almost everyone’s work. The only work that was somewhat affirmed was commented as “painted quite like Xu Mangyao.” Many times, what academia fears is not being criticized for painting too much like their teacher, but rather, the fear is that in the process of their work entering the market or the system, they may lose the competitive advantage they could have enjoyed because their work doesn’t resemble their teacher’s. This is an unspoken understanding, and even a collective scheme.

这个作品最终以微信推送的形式呈现,也正是对于这种现状的一种回应。不幸的是,大部分读者落入了对具体技术的盲目自信或自卑之中。陷入到了如“天啊,不会吧不会吧,这么明显的AI你们都看不出来吗?”与“哎呀,我真是被骗到了,没想到居然都是AI生成的”之类关于找不同的真假判断里。对我而言,AI并不是一个与人相对立的实体。AI应当作为一面镜子,可以让我们有一个更好的角度去理解何为人。

The final presentation of this work in the form of WeChat push notifications is a response to this situation. Unfortunately, most readers fall into the blind confidence or inferiority in specific technologies. They fall into judgments about finding differences in truth, such as “Oh my, can’t you all see that this is obviously AI?” and “Oh dear, I was really fooled, I didn’t expect it to be all AI-generated.” For me, AI is not an entity that is opposed to humans. AI should serve as a mirror, allowing us a better angle to understand what it means to be human.

还有一种评论是对AI生成图像过于冷酷的厌恶。许多人坚定地认为,机器和算法绝对不会有情感,因此他们生成的作品也绝对不会含有情感。然而,这里有一个难以忽视的问题,那就是我们自然而然地将“我们(人类)”与“它们(人工智能)”对立起来。但在我看来,我更愿意将“我”与“除我以外的所有事物”作为相区别的两个主体。归根结底,我们又如何知道,其他人类是否真的和我们一样有情感,而不是模拟出来的呢?

Another comment is the disdain for the coldness of AI-generated images. Many people firmly believe that machines and algorithms will never have emotions, so the works they generate will definitely not contain emotions. However, there’s a hard-to-ignore issue here, which is that we naturally set “us (humans)” against “them (artificial intelligence).” But from my point of view, I would rather regard “me” and “everything else but me” as two distinct subjects. After all, how do we know for sure that other humans really have emotions like us and are not just simulating them?

在诸多留言当中,有一条我感触很深。“我很自然地忽略掉了所有疑点和破绽,和ai的作品共了情。我在寻找隐喻,在只看到了自己想看到的东西。”是的,与其纠结于此,不如“耳得之而为声,目遇之而成色”。机器学习所生成的信息,如同一个平行时空中的无尽藏海。我们明明已经在历史长河中经历了如此多的“何为艺术”的讨论,诸如:有声电影不能叫电影,摄影必须得是胶片的,不押韵的不能称之为诗……但在大多数情况下,本体论者终将被时间打得体无完肤。

Among many comments, there’s one that I feel deeply about. “I naturally ignored all doubts and flaws, and empathized with the AI’s work. I was looking for metaphors, only seeing what I wanted to see.” Yes, rather than obsessing over this, it’s better to “hear it and turn it into sound, meet it with the eye and turn it into color.” The information generated by machine learning is like an endless sea in a parallel time and space. We’ve already had so many discussions about “what is art” in the long river of history, such as: talkies can’t be called movies, photography has to be film, anything not rhymed can’t be called poetry… But in most cases, the essentialists will be beaten by time beyond recognition.

画家张中阁有一句话让我记了很多年,“绘画可能一部分属于艺术”。绘画除去所谓的艺术的部分,可能还是技术、巫术,是奢侈品、投资工具,是晋升通道,是体力劳作,是时间,是对有毒的颜料与媒介剂的被动吸入。绘画中有非艺术的部分,正如AI艺术有后人类的成分。但这并不代表最终的结果一定是冰冷、无趣、不值一提的。也许我们可以抛开框架与背景,暂停观念与逻辑,回归到最简单最直接的对于作品的观看之中。艺术可能一部分属于人类。

The painter Zhang Zhongge once said something that I’ve remembered for many years, “Painting may be partially considered art.” Besides the so-called art part, painting could also be technology, magic, luxury, an investment tool, a promotion channel, physical labor, time, passive inhalation of toxic paints and mediums. The non-artistic part in painting is just like the post-human elements in AI art. But this doesn’t mean that the final outcome has to be cold, boring, and insignificant. Perhaps we can set aside frames and backgrounds, pause concepts and logic, and return to the simplest and most direct viewing of the work. Art may be partially human.

还有一点比较让我在意的是,在几百条留言之中,居然没有一条是关于人文学院的。究竟是因为大家对于艺术史领域较为陌生,还是文字天然没有图像那么受人关注?抑或是说知识本身其实是种幻象?

Another point that concerns me is that among hundreds of comments, not one was about the humanities. Is it because everyone is unfamiliar with the field of art history, or because text naturally doesn’t attract as much attention as images? Or could it be that knowledge itself is actually an illusion?

最后,如果我告诉你,本文其实是由我写的约150字的提示词出发,用ChatGPT自动生成的文章,你是否感到了愤怒,觉得浪费了好几分钟白读了一场?但如果我又告诉你这其实只是个玩笑,我仍然一字一句花了不少功夫才写出来的呢?对这篇文章而言,对你自身来说,到底有何区别?

Finally, if I tell you that this article is actually generated by ChatGPT based on a prompt of about 150 words written by me, would you feel angry, thinking that you wasted several minutes reading for nothing? But what if I tell you it was just a joke, and I still spent a lot of effort to write it, word by word? For this article, for you yourself, what is the actual difference?